Welcome to the World’s Worst Dinner Party

Picture this: you stumble into a garden where three lunatics are having tea at a table that clearly hasn’t been cleared in weeks. They’re solving riddles with no answers, arguing about time, and occasionally stuffing a dormouse into a teapot. There’s no room at an obviously empty table. Nothing makes sense. Everyone’s rude. The tea is probably cold.

Welcome to the Mad Tea Party, one of the most iconic scenes in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”—and possibly the most savage political takedown Lewis Carroll ever wrote.

On the surface, it’s just delightful chaos: the Mad Hatter, the March Hare, and the sleepy Dormouse engaged in the kind of nonsensical conversation that makes you question your own sanity. They ask impossible riddles (“Why is a raven like a writing desk?”), celebrate un-birthdays, and treat time like a person they’ve personally offended.

But here’s the thing about Carroll: the man was incapable of writing something that was just whimsical. He was a mathematician who saw patterns, a social observer who noticed hypocrisy, and someone who lived through some truly bonkers Victorian politics. When he wrote the Mad Tea Party, he wasn’t just creating a memorable scene—he was roasting an entire political system.

The tea party isn’t just absurd for laughs. It’s absurd because Carroll looked at Victorian government, bureaucracy, and political discourse and thought, “You know what? This is actually insane. Let me show everyone by making it slightly more honest.”

Every ridiculous element of the scene—the circular conversations, the obsession with arbitrary rules, the characters who talk past each other, the complete absence of logic—it’s all a mirror held up to the political establishment of Carroll’s time. And honestly? It still reflects our politics today, which says something depressing about progress.

So grab your teacup (there’s no room, but sit down anyway), and let’s decode what’s really happening at the Mad Tea Party. Spoiler: it’s not really about tea.

Meet Your Hosts: A Politician’s Nightmare (Or Mirror)

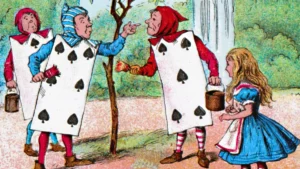

Let’s talk about our three main characters, because each one is doing some serious political work disguised as whimsical nonsense.

The Mad Hatter is arguably Carroll’s most pointed critique of politicians and government officials. This guy is obsessed with time—specifically, he’s stuck at 6 o’clock because he allegedly “murdered” Time by singing badly at a concert. Now Time won’t move for him, so it’s perpetually tea time.

Sound familiar? That’s Carroll satirizing politicians who are so disconnected from reality and so caught up in their own nonsense that they’re basically frozen in time. They can’t move forward because they’ve broken the fundamental rules of how things work. The Hatter’s anxiety about time mirrors a government that’s always in crisis mode but never actually progressing.

His nonsensical dialogue and erratic behavior? That’s Carroll showing us politicians who prioritize performance over substance. The Hatter talks constantly but says nothing of value. He asks riddles with no answers. He makes proclamations that don’t make sense. He’s basically every political speech you’ve ever had to sit through, except more honest about being pointless.

The March Hare represents the chaos and instability of political systems. His name alone is a clue—”mad as a March hare” was already a saying, referring to the wild behavior of hares during mating season. This character is pure unpredictability, making decisions that seem random and acting without any logical consistency.

Carroll’s showing us the irrationality of political decision-making when ideology trumps reason. The March Hare doesn’t engage in logical discourse; he just does whatever feels right in the moment, consequences be damned. Sound like any political figures you know? The March Hare is what happens when politicians let passion and impulse override good governance.

His frenzied behavior also reflects the instability of Victorian politics—the constantly shifting policies, the knee-jerk reactions to public opinion, the decisions that seem to contradict previous positions. It’s chaos pretending to be governance, and Carroll is not here for it.

The Dormouse is perhaps the saddest and most pointed allegory. This sleepy little creature represents the marginalized voices in society—the people who are talked over, ignored, and literally stuffed into teapots when they become inconvenient.

The Dormouse tries to tell stories and occasionally contributes wisdom, but the Hatter and March Hare constantly interrupt, silence, or dismiss him. When Carroll wrote this, huge portions of Victorian society had no political voice: women, the working class, anyone without property. They had thoughts and perspectives that could have been valuable, but they were drowned out by louder, more powerful forces.

The Dormouse’s sleepiness might also represent a population lulled into complacency, too comfortable or too exhausted to fight back against the system. Or maybe it’s just hard to stay engaged when no one listens to you anyway.

Together, these three create a perfect storm of political dysfunction: empty rhetoric (Hatter), irrational decision-making (March Hare), and silenced voices (Dormouse). It’s basically every failing of democratic governance wrapped up in a tea party.

And the brilliant part? Carroll makes them likeable. We remember the Mad Tea Party fondly. We quote it. We dress up as these characters for Halloween. Carroll understood that satire works best when it’s charming enough that people don’t realize they’re being criticized until they think about it later.

Tea, Taxes, and Why Everyone Was Mad

Now let’s talk about why this scene specifically involves tea. Because in Victorian England, tea wasn’t just a beverage—it was a political flashpoint.

The British government absolutely loved taxing tea. It was a stable source of revenue because everyone drank it, from aristocrats to factory workers. But those taxes were hefty, and people were not happy about it. (Americans may have some historical memory of tea tax issues, though their solution was more dramatic and involved a harbor.)

The Mad Tea Party is Carroll’s way of highlighting the absurdity of tax policy and bureaucracy. Think about it: the characters are literally stuck in a perpetual tea time, unable to move forward, cycling through the same nonsensical conversations over and over. That’s life under oppressive bureaucracy—you’re trapped in a system that makes no sense, forced to participate in rituals that benefit someone else while you just get more frustrated.

The circular nature of the tea party conversations mirrors the circular nature of trying to deal with government bureaucracy. Alice tries to engage logically with the characters, asking reasonable questions and making valid points. But she gets nowhere because the system isn’t designed to make sense—it’s designed to perpetuate itself.

“Why is a raven like a writing desk?” The Hatter asks, and never provides an answer because there isn’t one. That’s Carroll showing us political discourse where questions are asked but never answered, where debates happen but nothing gets resolved, where the whole performance is just theater with no substance.

The endless cups of dirty tea, the constant moving to new seats at the table, the refusal to actually clean anything—it’s all metaphor for a bureaucratic system that creates work without creating value. Why wash the dishes when you can just move to a new spot and grab a fresh cup? Why fix systemic problems when you can just shuffle people around and call it progress?

And the tea tax element adds another layer: citizens are essentially paying for the privilege of participating in this absurd system. You’re taxed on your tea, which funds a government that then subjects you to more nonsense. The Mad Tea Party is what happens when the people paying for the party realize the party is terrible and the hosts are ridiculous, but you’re stuck there anyway because leaving isn’t really an option.

Carroll, who was incredibly detail-oriented and deliberate in his writing, didn’t choose tea randomly. He chose it because his contemporary readers would immediately connect it to taxes, government overreach, and the frustrations of dealing with an unresponsive political system.

The Mad Tea Party is basically Carroll saying, “You know how dealing with the government feels completely insane and pointless? Let me show you what that looks like literally.” And then he did, and it was perfect.

Why This Still Hits Different Today

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: the Mad Tea Party is still relevant because political absurdity is apparently timeless.

The circular conversations that go nowhere? Turn on any political debate. The riddles with no answers? Listen to any politician dodge a direct question. The obsession with arbitrary rules while ignoring actual problems? Check your local bureaucracy. The silencing of marginalized voices? Still happening.

Carroll’s satire was so effective because he identified fundamental flaws in how power operates, not just specific Victorian issues. He showed us that when systems become more concerned with maintaining themselves than serving people, you get the Mad Tea Party—a pointless ritual that frustrates everyone involved but continues because no one knows how to stop it.

Modern political discourse often feels exactly like the tea party. We have the same conversations over and over. Politicians ask rhetorical questions they don’t intend to answer. Policy discussions devolve into nonsense. The people most affected by decisions are the ones least likely to be heard. And everyone’s kind of mad but we’re all still sitting at the table because what else are we going to do?

The tea party’s chaotic atmosphere—where logic is abandoned in favor of performance, where substance matters less than style, where actual problems are ignored in favor of theatrical arguments—that’s not uniquely Victorian. That’s just politics.

Carroll’s genius was recognizing that you can critique power more effectively through absurdism than through straightforward criticism. If he’d written a serious political essay about government dysfunction, it would have been forgotten within a decade. Instead, he wrote about a mad tea party, and we’re still talking about it 150+ years later.

The legacy of this scene is that it gives us a framework for recognizing and calling out political absurdity. When you see politicians engaging in obviously pointless debates, you can think, “This is some Mad Tea Party nonsense.” When bureaucracy seems designed to confuse rather than help, that’s the tea party. When voices are silenced in favor of louder, less informed ones, there’s the Dormouse getting stuffed in a teapot again.

Literature has this incredible power to outlast the specific moment it’s critiquing and become a universal tool for understanding power dynamics. Carroll didn’t just write about Victorian politics—he wrote about how politics works when it’s broken, regardless of era or location.

The Never-Ending Tea Party

The Mad Tea Party doesn’t have a resolution. Alice eventually gets frustrated and leaves, but the Hatter, March Hare, and Dormouse are still there, stuck in their endless loop. That’s not accidental—it’s Carroll’s final point.

Political dysfunction doesn’t fix itself. Broken systems perpetuate themselves. The tea party continues whether Alice participates or not, just like political absurdity continues whether you engage with it or check out entirely. The characters don’t learn, don’t change, don’t improve. They’re stuck, and they’ll stay stuck.

But here’s where Carroll offers something hopeful: Alice leaves. She recognizes the absurdity, refuses to play along anymore, and walks away to find something better. She doesn’t fix the tea party, but she doesn’t let it trap her either.

Maybe that’s the real message: you can’t always fix broken systems from within, especially when the system is invested in staying broken. But you can recognize absurdity when you see it, refuse to treat it as normal, and keep moving forward even when others are stuck.

The Mad Tea Party serves as both warning and invitation. Warning: this is what happens when politics becomes performance, when bureaucracy serves itself instead of people, when voices are silenced and logic is abandoned. Invitation: you don’t have to accept this as normal. You can call it out. You can refuse to participate in the absurdity.

Carroll wrapped this critique in whimsy and charm, making it accessible and memorable. He understood that the best satire doesn’t just point out problems—it makes you see them so clearly that you can’t unsee them. Once you recognize the Mad Tea Party in real political discourse, you’ll notice it everywhere.

So the next time you’re watching political theater that makes no sense, where the same arguments happen on repeat, where nothing gets resolved and nobody seems to care—remember: you’re at the Mad Tea Party. The question is whether you’ll grab a teacup and join in, or follow Alice’s example and find a better table.

The Tea That Keeps on Giving

What makes the Mad Tea Party brilliant is that it works on every level. Kids enjoy the silliness. Teenagers appreciate the rebellious absurdity. Adults recognize the political commentary. Scholars write dissertations about the layers of meaning.

Carroll created a scene that’s simultaneously children’s entertainment, political satire, philosophical inquiry, and social criticism. That’s incredibly difficult to pull off, and the fact that it still works 150+ years later proves just how well he did it.

The scene has become part of our cultural vocabulary. We reference it when we want to describe chaotic meetings, pointless arguments, or situations that make no sense. “This is like the Mad Tea Party” is immediately understood, even by people who’ve never read the book.

That’s the power of great satire: it transcends its original context and becomes a tool for understanding similar situations in any era. Carroll’s Victorian-era critique of tea taxes and political dysfunction has become a universal symbol of broken systems and absurd bureaucracy.

And maybe that’s the real legacy: Carroll showed us that you can fight power with imagination, critique systems with creativity, and reveal uncomfortable truths through whimsy. The Mad Tea Party is proof that the pen is mightier than the sword—especially when that pen is dipped in tea and wielded by a mathematical genius with a gift for satire.

So here’s to Lewis Carroll, who looked at Victorian politics and thought, “I can make this weirder by making it more honest.” He created a scene that entertains children while skewering the powerful, that makes us laugh while making us think, and that remains devastatingly relevant in ways we wish it weren’t.

The Mad Tea Party continues, in literature and in life. The least we can do is recognize it for what it is: a brilliant, timeless critique wrapped in a delightful, memorable package.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to find a cleaner teacup. This one’s been used too many times without washing, and that’s starting to feel a little too on-the-nose.

No room! No room! Indeed.