When Your Handmade Gift Accidentally Becomes Literary History

Imagine making a scrapbook for a friend’s kid. You write a silly story, add some doodles, bind it yourself, and give it as a Christmas present. Nice gesture, right?

Now imagine that homemade book eventually becomes one of the most famous works in English literature, gets adapted into countless films, inspires a multi-billion-dollar franchise, and is still being analyzed by scholars 150+ years later.

That’s essentially what happened to Lewis Carroll.

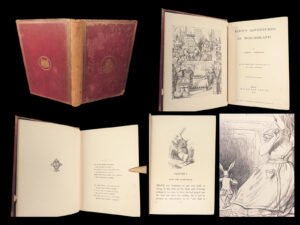

In 1864, Carroll (whose day job was being Charles Dodgson, Oxford math lecturer) gave a handmade manuscript to Alice Liddell, the daughter of his boss. The book was called “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground,” and it was a cleaned-up, illustrated version of a story he’d improvised during a boat trip two years earlier.

Carroll wrote it by hand. He drew the illustrations himself (and they’re… let’s just say enthusiastic rather than professional). He bound it himself. It was a one-of-a-kind, handcrafted labor of love, meant for an audience of exactly one person: Alice Liddell.

That homemade gift is now worth millions of dollars. It’s housed in the British Library as a national treasure. It’s been digitized, analyzed, exhibited, and studied by countless scholars. And it spawned “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” which became one of the most influential books ever written.

Talk about overdelivering on a Christmas present.

The story of “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” is fascinating because it shows the entire creative process in miniature: from improvised storytelling to written manuscript to published phenomenon. It’s also a beautiful example of Victorian book-making, a testament to the power of handcrafted art, and evidence that sometimes the most personal gifts become the most universal stories.

Let’s dive into the story of the manuscript that started it all—the handmade book that accidentally changed literature.

A Boat Trip That Changed Everything

The origin story of Alice is almost as famous as the book itself. On July 4, 1862 (yes, the Fourth of July—make of that what you will), Carroll went on a boat trip with the Liddell family on the River Thames. The party included three Liddell sisters: Lorina, Alice, and Edith.

During the trip, the girls demanded a story. Carroll, who frequently entertained them with improvised tales, began narrating an adventure about a girl named Alice who falls down a rabbit hole. He made it up as he went along, pulling from the environment around them, the girls’ reactions, and his own considerable imagination.

Alice Liddell loved it. She loved it so much that she asked Carroll to write it down for her. And Carroll, who was clearly incapable of doing anything halfway, didn’t just jot down some notes. He spent over two years crafting a complete manuscript, writing it by hand, creating illustrations, and binding it into a book.

This is important context: Carroll wasn’t writing for publication. He wasn’t trying to create a commercial product or literary masterpiece. He was making a gift for a specific child who’d asked for the story. Every decision he made—what to include, how to illustrate it, how to present it—was with Alice Liddell in mind.

That personal connection shows in every page of “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground.” The story is intimate, playful, and filled with inside jokes and references that the Liddell sisters would have understood. Carroll wasn’t writing for a general audience; he was writing for Alice, Lorina, and Edith.

The manuscript he created was 90 pages long, with 37 of his own illustrations. He wrote it in his careful, neat handwriting. The illustrations are charming in their amateurishness—Carroll was a photographer and mathematician, not a trained artist, and it shows. But they have personality and enthusiasm, which counts for a lot.

Carroll gave the finished manuscript to Alice as a Christmas gift in November 1864 (he’d started it in 1862, so yes, this “gift” took him over two years to complete). The title page read: “A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer Day.”

Can you imagine being Alice Liddell, receiving this hand-crafted book with her name literally in the title, filled with adventures featuring a character named after her? It must have felt like the most special gift in the world.

And it was. Just not in the way anyone expected.

The Manuscript: A Victorian Passion Project

Let’s talk about the manuscript itself, because “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” is a fascinating artifact even beyond its literary significance.

Carroll wrote the entire thing by hand in brown ink. His handwriting is remarkably neat and consistent—he was clearly taking this seriously. The text fills 90 pages, with careful spacing and layout that shows real attention to design.

But here’s where it gets interesting: Carroll wasn’t just a writer; he was a photographer with an eye for visual composition. Even though his drawing skills were… enthusiastic… he understood how text and image should work together on a page. The illustrations aren’t just stuck randomly into the manuscript—they’re integrated with the text, creating a visual rhythm that guides the reader through the story.

Carroll’s illustrations have this wonderful amateur quality. They’re not technically sophisticated—proportions are weird, perspectives are wonky, and sometimes characters look a bit off. But they have charm and personality. His Alice has this determined expression in every drawing, which actually captures the character better than more polished illustrations might have.

The Mad Hatter looks slightly unhinged (appropriate). The Cheshire Cat’s grin is genuinely creepy (also appropriate). The Queen of Hearts is properly intimidating. Carroll might not have been a professional artist, but he understood his own characters and translated them to the page with real affection.

The typography is also worth noting. Carroll used different sizes and styles of handwriting to create emphasis and rhythm. Important phrases are larger. Whispered dialogue is smaller. The text itself becomes part of the visual storytelling, which shows sophistication in how he thought about the reading experience.

What’s remarkable is the craftsmanship. This wasn’t a rough draft—this was a finished product, made with care and attention to detail. Carroll bound it himself (or had it bound to his specifications), creating a physical object that was meant to last.

And it has lasted. The manuscript survived over 150 years, changed hands multiple times (more on that in a moment), and is now preserved as a cultural treasure. Not bad for what started as a DIY project.

The manuscript represents Victorian book-making at its most personal. During this era, handmade gifts were valued specifically because they showed effort and care. Mass production was changing society, making everything more available but less personal. A handmade book was a statement: “I spent time on this. I made this specifically for you.”

Carroll’s manuscript embodies this perfectly. Every page represents hours of work—writing, illustrating, laying out, binding. It’s not just a story; it’s a physical manifestation of friendship and affection.

From Personal Gift to Publishing Phenomenon

Here’s where the story gets really interesting: how did a private, handmade gift for one child become a published bestseller?

Friends and colleagues who saw the manuscript encouraged Carroll to publish it. They recognized that the story had appeal beyond its original recipient. Carroll was initially hesitant—remember, this was written for Alice, filled with personal references and inside jokes. Could it work for a general audience?

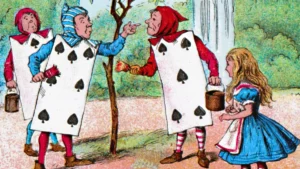

Eventually, he decided to try. But Carroll being Carroll, he couldn’t just publish what he’d already written. No, he had to expand it, revise it, add new episodes, remove some personal references, and commission professional illustrations from Sir John Tenniel (an established artist for Punch magazine).

“Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” was published in 1865, and it was significantly different from “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground.” Carroll added about 50% more content, including entire scenes that weren’t in the original (like the Cheshire Cat, who became one of the most iconic characters but wasn’t in the handmade version—wait, what?).

Actually, I need to correct that: the Cheshire Cat was in the original manuscript, but in a much smaller role. Carroll expanded the character significantly for publication, recognizing its potential. He also added the Mad Tea Party, which became one of the most famous scenes but was just briefly mentioned in the manuscript.

Tenniel’s professional illustrations replaced Carroll’s amateur drawings. While we appreciate Carroll’s originals now for their charm, Tenniel’s images became the definitive visualization of Wonderland for generations. Those are the illustrations everyone remembers.

The published version was a huge success. It was one of the first children’s books written purely for entertainment rather than moral instruction, and readers loved it. It went through multiple printings, sold thousands of copies, and established Carroll as a major literary figure.

But here’s the beautiful part: the success of the published book didn’t erase the manuscript. If anything, it made the handmade original more valuable and significant. Collectors and scholars became fascinated with seeing Carroll’s first version, understanding how the story evolved, and appreciating the personal nature of the original gift.

Alice Liddell kept the manuscript for decades. But in the 1920s, facing financial difficulties, she sold it at auction. It sold for £15,400 (about $77,000), which was a staggering amount for a manuscript at the time and set records for book auctions.

The manuscript changed hands again, eventually being purchased by American collectors. During World War II, it was in the United States, safe from the bombing of London. After the war, a group of American benefactors purchased it and presented it to the British Library as a gift to the British people in gratitude for their resistance during the war.

So this manuscript—this handmade Christmas gift—became a symbol of international friendship and cultural heritage. It went from Alice Liddell’s bookshelf to being a national treasure housed in one of the world’s great libraries.

That’s quite a journey for a DIY project.

Why Handmade Books Still Matter

In our digital age, the concept of a handmade book might seem quaint or outdated. Why spend hours crafting something by hand when you can type it up, print it, or publish it digitally in minutes?

But that’s exactly why handmade books matter: because they can’t be replicated or mass-produced. Each one is unique, carrying the physical trace of its creator in every pen stroke and brushstroke.

“Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” embodies this perfectly. When you look at the manuscript (or high-quality reproductions), you’re seeing Carroll’s actual handwriting, his actual illustrations, his actual artistic decisions. You can see where he paused, where he made corrections, where he put extra effort into a particular drawing.

There’s an intimacy to handmade books that printed versions can’t replicate. The physical object carries meaning beyond its content. It’s evidence of time spent, care taken, and personal connection maintained.

Modern readers might struggle to understand this in an era of ebooks and print-on-demand. But think about it this way: would you rather receive a mass-produced greeting card or one that someone made by hand specifically for you? The sentiment might be the same, but the handmade version carries additional meaning because of the effort involved.

Victorian culture understood this deeply. Handmade gifts were valued precisely because they represented investment of time and skill. In an increasingly industrialized world, handcrafted items became markers of personal relationships and individual care.

Carroll’s manuscript exists at this intersection of craft and art. It’s literature, yes, but it’s also a physical artifact—a crafted object that has aesthetic value independent of its text.

Libraries and museums recognize this, which is why they preserve these manuscripts so carefully. They’re not just preserving the text (which exists in countless printed editions) but the physical object itself, with all its historical and artistic significance.

The British Library treats “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” as a treasure. It’s been digitized so people worldwide can view it, but the physical manuscript is carefully maintained under controlled conditions. It’s exhibited occasionally, allowing visitors to see the actual pages Carroll created.

This preservation work ensures that future generations can experience something that can’t be reduced to digital reproduction: the tangible connection to Carroll’s creative process, the physical presence of a 150-year-old handmade book, the real object that connected an author to his young friend.

The Legacy of a Christmas Gift

“Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” started as a Christmas gift and became literary history. That transformation tells us something important about creativity, connection, and the unpredictable nature of influence.

Carroll had no idea his handmade book would lead to one of the most famous works in English literature. He was just trying to make Alice Liddell happy, to preserve a story she’d enjoyed, to create something special for someone he cared about.

The sincerity of that intention shows in every page. The manuscript feels personal because it was personal. Carroll wasn’t trying to write a masterpiece or create commercial success—he was just telling a story for a specific child.

And somehow, that personal specificity became universal. The story that was written for Alice Liddell resonated with millions of readers. The handmade gift became a cultural phenomenon. The private joke became public treasure.

There’s a lesson here about creativity: sometimes the most authentic work comes from not trying to please everyone, but from focusing on delighting one specific person. Carroll wrote for Alice, and in doing so, created something that would delight countless others.

The manuscript also reminds us of literature’s journey from private to public. Every published book starts somewhere personal—in an author’s imagination, experience, or relationships. “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” makes that process visible, showing the intimate origins of what would become a widely shared cultural artifact.

Today, you can view digital scans of Carroll’s manuscript online. The British Library has made it accessible to anyone with internet connection. You can see his handwriting, study his illustrations, and read the story as Alice Liddell first experienced it.

But the physical manuscript remains special—a tangible link to the moment when a Victorian mathematician decided to write down a story for a friend’s daughter, not knowing he was creating something that would outlast them all.

That’s the power of handcrafted literature: it carries both the story and the story behind the story, the text and the context, the words and the love that prompted someone to write them down.

A Gift That Keeps Giving

Lewis Carroll made Alice Liddell a book. That book inspired a published novel. That novel became a cultural phenomenon. That phenomenon continues to inspire new adaptations, interpretations, and creative works over 150 years later.

All because a mathematician wanted to make a child happy.

“Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” proves that the most personal gestures can have the most universal impact. Carroll’s handmade manuscript, created with patience and affection for one specific reader, eventually reached millions.

The manuscript reminds us why handcrafted books matter: not just as aesthetic objects or historical artifacts, but as physical manifestations of human connection and creative expression. In a world of mass production and digital reproduction, handmade books represent something irreplaceable—the direct link between creator and creation, between giver and recipient.

Carroll gave Alice a book. Alice gave the world a glimpse into how classics are born. And we all benefit from the preservation of this handmade treasure, this Christmas gift that accidentally changed literary history.

Not bad for a DIY project.

The next time you make something by hand for someone you care about—a card, a drawing, a story—remember: you’re participating in a tradition that gave us Wonderland. Your handmade gift might not become a literary classic (probably won’t, statistically speaking), but it will carry something no mass-produced item ever can: the physical trace of your time, effort, and care.

That’s magic enough.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go make a handmade book. Just in case it accidentally becomes priceless cultural treasure in 150 years.

You never know.