When “Mad as a Hatter” Was a Medical Diagnosis

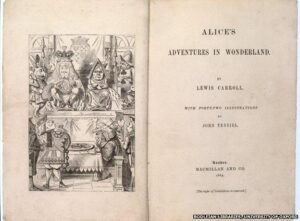

Let’s start with something cheerful: the Mad Hatter, that delightfully eccentric character from “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” is based on people who were literally dying from occupational poisoning. Fun, right?

Here’s the thing about Lewis Carroll—the man couldn’t just create a whimsical character for laughs. No, he had to base it on actual Victorian-era industrial tragedy. The Mad Hatter, with his nonsensical riddles, eternal tea party, and general chaos, seems like pure fantasy. But the phrase “mad as a hatter” was real Victorian slang, and it referred to something genuinely horrifying: the neurological damage suffered by hat-makers who were slowly being poisoned by mercury.

So when you’re watching the Mad Hatter ask “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” and thinking, “Haha, what a silly character,” remember that Carroll was actually depicting symptoms of severe mercury poisoning. The tremors, the mood swings, the erratic behavior, the cognitive dysfunction—all real symptoms of what became known as “Mad Hatter Disease.”

The Mad Hatter is charming and memorable and has been portrayed by everyone from Disney animators to Johnny Depp. But he’s also a walking metaphor for industrial capitalism’s complete disregard for worker safety. He’s the Victorian equivalent of a character whose quirky personality is actually just untreated occupational illness.

Carroll took a tragic reality—workers suffering from mercury poisoning—and transformed it into a character that’s become beloved worldwide. It’s kind of genius, but also deeply unsettling once you know the truth. The whimsy has a body count.

Let’s dive into the grim reality behind one of literature’s most iconic characters, shall we? Fair warning: this gets dark. But it’s important, because the Mad Hatter’s legacy connects to labor rights, occupational safety, and mental health awareness in ways that are still relevant today.

Welcome to the tea party. The tea is poisoned, the host is dying, and the whole thing is a metaphor for how society treats workers. Enjoy!

How to Make a Hat (and Destroy Your Brain)

The hat-making process in the 1800s was actually fascinating—right up until the part where it started killing people. Let me walk you through how Victorian society decided that looking good in a top hat was worth sacrificing human health.

First, hatters would acquire animal fur, typically from rabbits or beavers. This fur needed to be transformed into felt, which required cleaning, carding (basically combing the fibers), and matting them together. So far, so good. Just regular artisan craftsmanship, right?

Here’s where it gets problematic: to make really high-quality felt, hatters discovered that treating the fur with mercury—specifically mercuric nitrate—made it much more pliable and easier to work with. The mercury-treated fur could be molded into perfect shapes, held its form better, and had a superior texture that consumers loved.

And by “discovered,” I mean someone figured this out, it worked great for the hats, and everyone collectively decided not to think too hard about what it might be doing to the people working with mercury all day, every day, in poorly ventilated workshops.

The process involved brushing mercury compounds onto the fur, which meant hatters were constantly exposed to mercury vapors. They’d inhale it while working. It would get on their hands. They’d absorb it through their skin. Day after day, year after year, the mercury would accumulate in their bodies, slowly destroying their nervous systems.

But hey, the hats looked amazing. Priorities, right?

The irony is brutal: mercury made hat-making easier and more profitable, which meant more people entered the trade, which meant more people getting poisoned. The very thing that made the industry successful was also what made it lethal. It’s capitalism in microcosm—a solution that benefits the product and the profit while destroying the people doing the work.

What makes this even worse is that people knew. Maybe not the full extent of the damage, but workers and their families noticed that hatters developed strange symptoms. They shook. They became irritable and erratic. Their personalities changed. Their minds deteriorated. The pattern was obvious.

But mercury made better hats, and better hats made more money, so the industry just… kept using it. They called the symptoms “hatter’s shakes” or noted that hatters went “mad,” and then continued poisoning people because addressing the problem would have been expensive and inconvenient.

This wasn’t some medieval practice done in ignorance. This was the 1800s—the age of scientific advancement and industrial progress. People were inventing trains and telegraphs and developing modern medicine. And yet, hat-makers were being slowly poisoned because profit mattered more than people.

The practice became so widespread and the symptoms so common that “mad as a hatter” became a colloquial expression. Think about that: the occupational hazard was so severe and so common that society just incorporated it into everyday language and moved on.

Carroll didn’t have to invent the Mad Hatter’s madness. He just had to look at the hat-making industry and report what he saw.

When Your Job Literally Makes You Crazy

Let’s talk about what mercury poisoning actually does to a person, because the symptoms of “Mad Hatter Disease” are legitimately terrifying—and they explain a lot about Carroll’s character.

Tremors were usually the first noticeable symptom. Hatters would develop involuntary shaking, particularly in their hands. Imagine trying to do delicate craftwork while your hands won’t stop trembling. The very thing that made you skilled at your job becomes impossible as the job destroys your ability to do it.

Mood swings came next. Mercury affects the brain’s neurotransmitters, causing wild emotional fluctuations. Hatters would go from irritable to depressed to euphoric without warning. Their personalities would change. The person their family knew would gradually disappear, replaced by someone unpredictable and difficult to recognize.

Hallucinations were common in severe cases. Visual distortions, auditory hallucinations, paranoia—the Mad Hatter’s seemingly nonsensical perceptions weren’t just whimsy. They were symptoms. When the Hatter acts like he’s experiencing a reality different from everyone else’s, that’s not just Carroll being creative. That’s Carroll depicting actual mercury poisoning.

Cognitive decline was perhaps the cruelest symptom. Memory loss, difficulty concentrating, problems with reasoning and problem-solving—the mind literally deteriorating. Hatters would lose the ability to think clearly, to remember important information, to function mentally in ways they once took for granted.

Other symptoms included excessive salivation, tooth loss, kidney damage, and a metallic taste that never went away. The tremors got worse over time. The cognitive decline was progressive. There was no cure, no treatment, just a slow descent into neurological chaos.

And here’s the truly dark part: Victorian society didn’t understand this as poisoning. They saw it as madness. As mental illness. As personal failing or bad luck or divine punishment or just something that happened to hatters, who everyone knew were a bit odd.

The stigma around mental illness was already severe, and mercury poisoning made it worse. People suffering from what was actually occupational poisoning were treated as if they were simply “mad”—locked away, dismissed, mocked. The Mad Hatter in Carroll’s story is treated as ridiculous, his symptoms played for laughs, because that’s how Victorian society treated actual hatters suffering from mercury poisoning.

Carroll’s genius was in capturing this reality so perfectly that the character became iconic, but also in coding it so subtly that people could enjoy the whimsy without confronting the tragedy. The Mad Hatter is entertaining because we can laugh at the madness without thinking about the mercury.

But once you know, you can’t unknow. Every time the Hatter acts erratically, you’re watching symptoms of industrial poisoning. Every tremor, every nonsensical statement, every mood swing—it’s all there in the historical record of what mercury did to real people.

The Mad Hatter isn’t just mad. He’s poisoned. And that changes everything about how we read the character.

The Legacy: From Tragedy to Icon (and Back Again)

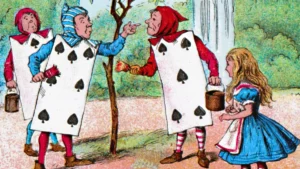

The Mad Hatter has become a cultural phenomenon. He’s been adapted, reimagined, merchandised, and memed into oblivion. Disney made him colorful and whimsical. Tim Burton made him tragic and sympathetic. Hot Topic has probably sold a million Mad Hatter-themed products to teenagers exploring their quirky side.

But here’s what’s interesting: as the character became more famous, the original context got lost. Most people know “mad as a hatter” is a saying, but they don’t know it’s about occupational mercury poisoning. They think the Mad Hatter is just a fun, eccentric character, not a representation of industrial victims.

That’s both good and bad. Good because the character has transcended his origins and become something new and meaningful in different contexts. Bad because we’ve essentially sanitized a critique of labor conditions into pure entertainment.

Understanding the true story behind the Mad Hatter should make us think about worker safety, both historically and today. The hat-making industry’s use of mercury is an extreme example, but it’s part of a larger pattern: industries prioritizing profit over people, knowing their practices harm workers, and doing it anyway because it’s cheaper than the alternative.

Victorian hatters were expendable. Their health didn’t matter as much as hat quality. Their symptoms were mocked rather than treated. The poisoning was common knowledge, and society just… accepted it. “That’s just what happens to hatters” became an acceptable explanation for preventable suffering.

Sound familiar? Because we still do this. We still have occupational hazards that we collectively shrug about. We still have industries that prioritize profit over safety. We still have workers whose health is treated as an acceptable cost of doing business.

The difference is that now we (theoretically) have regulations, safety standards, workers’ rights, and OSHA. But those protections came from recognizing that what happened to hatters—and miners, and factory workers, and countless other laborers—was unacceptable.

The Mad Hatter’s legacy, when properly understood, is a reminder that whimsy can carry weight, that fiction can illuminate reality, and that we have a responsibility to learn from the tragedies we’ve turned into entertainment.

Mental Health, Then and Now

One of the most important aspects of the Mad Hatter’s story is what it reveals about attitudes toward mental health, both in Carroll’s time and our own.

Victorian society had virtually no understanding of mental illness. What we now recognize as neurological damage from toxic exposure was interpreted as madness, moral failing, or possession. People suffering from mercury poisoning weren’t getting medical treatment—they were being ostracized, institutionalized, or just left to deteriorate.

The stigma was crushing. Being labeled “mad” meant social death. It meant your testimony was worthless, your autonomy was forfeit, and your suffering was either ignored or treated as entertainment. The Mad Hatter’s character reflects this—he’s not taken seriously, his words are dismissed as nonsense, and he’s stuck in a perpetual tea party going nowhere.

Carroll was writing during a period of massive industrial growth, when occupational hazards were creating health crises that society was ill-equipped to handle. The symptoms of mercury poisoning looked like mental illness, but the cause was environmental and preventable. Yet instead of addressing the root cause, society just categorized the victims as “mad” and moved on.

We’ve made progress since then. We understand toxic exposure, neurological damage, and occupational illness better. We have worker protections (in theory) and mental health awareness campaigns. We know that mental health is real health, that symptoms have causes, and that people deserve treatment rather than mockery.

But we’re not done. Mental health stigma still exists. Occupational hazards still harm workers. Industries still prioritize profit over people. The conversation has evolved, but the fundamental issues the Mad Hatter represents haven’t been fully resolved.

What makes the Mad Hatter relevant today isn’t just the historical curiosity of mercury poisoning—it’s the ongoing struggle to protect workers, understand mental health, and hold industries accountable for the harm they cause.

The Tea Party Continues

The Mad Hatter sits at his eternal tea party, trapped in time, unable to move forward. His madness is permanent, his suffering endless, and his reality fundamentally altered by poison he never chose to be exposed to.

That’s not just a whimsical scene. It’s a metaphor for how industrial capitalism treats its workers: use them up, discard them when they break, and keep the party going with fresh victims.

Carroll captured this reality so perfectly that we’ve been quoting it for over 150 years. The Mad Hatter became iconic not despite his tragic origins, but because of how effectively Carroll transformed industrial horror into memorable fiction.

But the transformation shouldn’t make us forget the reality. Behind the whimsy is genuine suffering. Behind the memorable character are real people who were poisoned for profit. Behind the eternal tea party is an industry that valued hats more than health.

The Mad Hatter’s legacy is complex. He’s entertainment and education, whimsy and warning, beloved character and tragic symbol. He makes us laugh and makes us think—if we’re paying attention.

So the next time you see the Mad Hatter—in a movie, on merchandise, in a meme—remember: he’s not just mad. He’s poisoned. And the distinction matters, because it transforms a silly character into a powerful reminder of what happens when society values products over people.

The real history behind the Mad Hatter is dark, yes. But it’s also important. It’s a reminder that the price of progress shouldn’t be human suffering, that worker safety matters, that mental health deserves understanding rather than mockery, and that sometimes the most whimsical stories carry the heaviest truths.

Carroll gave us a character we remember. History gave us a reason to remember him right.

Now, who wants tea? Don’t worry—it’s mercury-free. Probably. I mean, regulations exist now. Mostly.

We’ve come a long way since the 1800s. But the Mad Hatter’s still at that table, still trembling, still trapped in time—a permanent reminder of what we should never forget.

Cheers to worker safety, mental health awareness, and literary characters that carry more weight than they first appear. And cheers to Lewis Carroll, who looked at industrial tragedy and thought, “I can make this matter by making it memorable.”

He was right. The Mad Hatter matters. Now you know why.