When Your Book Comes Home After 150+ Years

Imagine you wrote a book, kept your personal copy for years, and then after you died, that copy went on an adventure of its own—changing hands, crossing oceans, surviving wars, and eventually finding its way back to where it all started over a century later.

That’s exactly what happened to Lewis Carroll’s personal copy of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” And honestly, it’s almost as wild a journey as Alice’s trip down the rabbit hole.

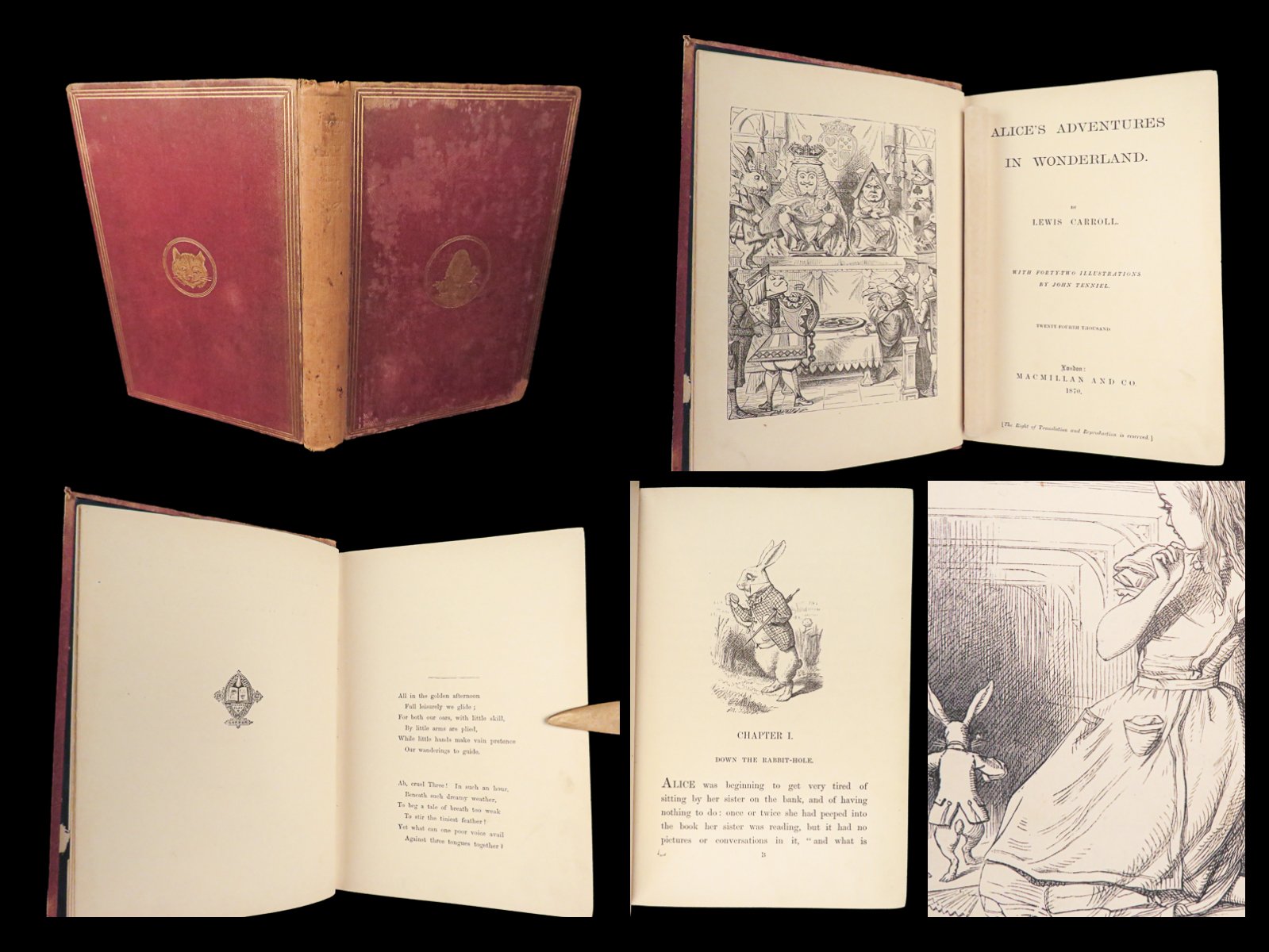

In 2024 (or recently, depending on when you’re reading this), Carroll’s own copy of his most famous work returned to Oxford—specifically to Christ Church, the college where he lived, worked, and first told the story that would become Wonderland. This wasn’t just any copy of the book. This was Carroll’s copy, the one he personally owned, possibly annotated, and kept as his own.

The return of this book is a big deal. Like, “major cultural event with ceremonies and scholarly excitement” big deal. Because this isn’t just a rare book returning to a library—it’s a piece of literary history coming home to the place where it was born.

Carroll spent most of his adult life at Christ Church. He taught mathematics there, took photographs in its halls, befriended the dean’s children in its gardens, and told the original Alice story during a boat trip on the nearby River Isis (which is what the Thames is called in Oxford, because Oxford has to be fancy about everything).

The story of Alice is inseparable from Oxford. And now, the physical object—Carroll’s personal copy—is back where it belongs, completing a circle that took over 150 years to close.

Let’s explore why this homecoming matters, what makes Christ Church and Oxford so integral to the Alice story, and how one book’s journey mirrors the enduring legacy of the tale it contains.

Oxford: Where the Magic Started

To understand why this book’s return is significant, you need to understand Carroll’s connection to Oxford. This wasn’t just where he worked—it was basically his entire adult life.

Charles Dodgson (Carroll’s real name) came to Christ Church as a student in 1851 and stayed for the rest of his life. He became a mathematics lecturer, a position he held for 26 years. Christ Church wasn’t just his workplace; it was his home, his social world, his creative incubator.

The college itself is stunning—one of Oxford’s grandest, with architecture that looks like it came straight from a fairy tale (or, you know, a fantasy novel about a girl in a strange world). It has a cathedral, magnificent halls, beautiful gardens, and the kind of Gothic grandeur that probably influenced Carroll’s imaginative landscapes.

But here’s what really matters: Christ Church is where Carroll met Alice Liddell. Her father, Henry Liddell, was the Dean of Christ Church, which meant the Liddell family lived in the Deanery on the college grounds. Carroll, as a fellow of the college, was part of the same social circle.

He befriended the Liddell children—particularly the three sisters: Lorina, Alice, and Edith. He would tell them stories, take them on outings, photograph them (Carroll was an accomplished photographer), and generally entertain them with his creative imagination.

The famous boat trip where Carroll first told the Alice story? That started from Oxford, went down the River Isis, and ended at Godstow, just a few miles away. The whole genesis of Wonderland happened within a few miles of Christ Church.

So when we say Carroll’s personal copy of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” has returned to Oxford, we’re talking about the book coming back to the literal physical place where the story was born. The gardens where Carroll walked with the Liddell sisters still exist. The river where he told the original tale still flows. The buildings where he lived and worked are still standing.

Having Carroll’s personal copy at Christ Church creates this incredible connection across time. You can stand in the same spaces Carroll occupied, look at the same architecture he saw, and now see the actual book he owned. It’s a tangible link to the moment of creation, preserved across 150+ years.

Oxford isn’t just background to the Alice story—it’s fundamental to it. The nonsensical logic of Wonderland might even reflect Carroll’s experience of Oxford’s peculiar traditions, ancient rules, and sometimes absurd academic hierarchies. Christ Church certainly had its share of eccentric characters who could have inspired the Mad Hatter or the White Rabbit.

The return of Carroll’s copy to this place isn’t just about preserving a book—it’s about reuniting an artifact with its origin story, bringing the object back to the landscape that inspired its creation.

Christ Church and the Bodleian: Oxford’s Literary Powerhouses

Now let’s talk about the institutions themselves, because Christ Church and the Bodleian Library aren’t just “some college and library”—they’re world-class cultural institutions with serious credentials.

Christ Church is one of the largest and most prestigious colleges at Oxford. It was founded by Cardinal Wolsey in 1525 (then refounded by Henry VIII because, you know, Henry VIII). Its chapel is actually Oxford Cathedral, making it the only college chapel in the world that’s also a cathedral. The dining hall inspired the Great Hall in the Harry Potter films. This place has gravitas.

But beyond the impressive architecture, Christ Church has been home to 13 British Prime Ministers, numerous scientists, writers, and thinkers. It’s an institution that takes its cultural and intellectual heritage seriously. Carroll is part of that heritage—he’s one of Christ Church’s most famous fellows, and the college has maintained his legacy carefully.

Having Carroll’s personal copy at Christ Church means it’s not just being preserved—it’s being contextualized. Visitors can see where Carroll lived (his rooms are now part of the college), walk through spaces he occupied, and now view his personal copy of his most famous work. It creates a complete experience of Carroll’s life and work.

The Bodleian Library, meanwhile, is one of the oldest libraries in Europe, established in 1602. It’s not just old—it’s important. It’s a legal deposit library, meaning it receives a copy of every book published in the UK. It holds over 13 million items. It’s been integral to Oxford’s academic life for over 400 years.

The Bodleian has one of the world’s most significant collections of rare books and manuscripts. Having Carroll’s personal copy in the Bodleian’s collections means it’s being preserved with the same care and expertise applied to medieval manuscripts, Shakespeare folios, and other irreplaceable cultural treasures.

These institutions aren’t just storing Carroll’s book—they’re safeguarding literary heritage. They’re making it accessible to scholars who want to study it, while preserving it for future generations. They have the expertise, resources, and commitment to ensure this book survives another 150 years and beyond.

The partnership between Christ Church and the Bodleian in preserving Carroll’s legacy is perfect. Christ Church provides the historical and cultural context—this is where Carroll lived and worked. The Bodleian provides the preservation infrastructure and scholarly access. Together, they create a complete ecosystem for understanding and appreciating Carroll’s work.

And let’s be honest: having your personal copy of your most famous book end up in one of the world’s great libraries, housed at the institution where you spent your life? That’s pretty good immortality. Carroll would probably appreciate the symmetry.

A Homecoming Worth Celebrating

When Carroll’s personal copy returned to Oxford, it wasn’t just quietly shelved in a library. Oh no. Oxford did what Oxford does best: threw a proper ceremonial celebration with all the academic pomp you’d expect from a 900-year-old university.

The donation was marked with a formal ceremony at the University of Oxford. This wasn’t some small gathering—we’re talking scholars, literary enthusiasts, university officials, and community members all coming together to celebrate. Because when a piece of literary history comes home, you make it an event.

The highlight? The unveiling of the book itself. Carroll’s personal copy was presented to the attendees, showcasing not just the book but any personal notes, annotations, or marks Carroll might have made. These personal touches transform a printed book into something intimate—evidence of how Carroll interacted with his own published work.

Imagine being able to see Carroll’s marginalia, his corrections, his thoughts on his own text. It’s like getting a peek into his mind, seeing how he reflected on the work that made him famous. That’s the kind of access that makes scholars weak in the knees.

But the celebration didn’t stop with the ceremony. Because this is Oxford, and Oxford knows how to milk a literary event for all its worth (affectionate).

Academic panels were organized featuring literary scholars discussing the themes, symbolism, and enduring impact of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. These weren’t just academic talks for specialists—they were public events designed to engage anyone interested in Carroll’s work. Discussions about the mathematical elements, the social satire, the philosophical questions, the narrative innovations—all the layers that make Alice such a rich text.

But here’s what’s actually wonderful: they didn’t just make it an academic affair. The events included interactive workshops for families and children. Storytelling sessions brought Alice’s adventures to life for young audiences. Creative art activities let kids engage with the world of Wonderland through drawing and imagination.

This is important because Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is, fundamentally, a children’s book. It’s been analyzed by scholars, adapted by filmmakers, and studied by academics—but it started as a story for children. Including kids in the celebration honors that origin.

Local bookshops got involved too, hosting readings and offering promotions on Carroll’s works. This turned a university event into a community celebration, spreading the literary love beyond academic circles.

The whole series of events accomplished something beautiful: it made a 150-year-old book feel alive and relevant. It connected Carroll’s Victorian-era creation to contemporary readers, showing that great literature doesn’t just survive in libraries—it lives in communities, classrooms, and imaginations.

Why One Book’s Journey Matters

You might be thinking, “Okay, but it’s just a book. Why does it matter where it’s kept?”

Fair question. Let me explain why Carroll’s personal copy returning to Oxford is more significant than just “old book goes to library.”

First, there’s the historical significance. This isn’t just any copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—it’s Carroll’s own copy. It might contain his annotations, his corrections, his thoughts on his published work. It’s a primary source for understanding how Carroll viewed his own creation.

Scholars can study this copy to understand Carroll better. Did he notice errors in the published text? Did he have second thoughts about certain passages? Did he make notes for future editions? Every mark in this book is data about Carroll’s creative process and relationship with his work.

Second, there’s the symbolic power of objects. Yes, the text of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is available everywhere—you can download it for free right now. But the physical object that Carroll owned carries meaning beyond its text. It’s a tangible connection to the author, a real thing he touched and owned.

In our digital age, we’re learning that physical objects still matter. There’s something about the real thing—the actual paper, the actual binding, the actual book that existed in Carroll’s world—that digital reproduction can’t capture. It’s the difference between seeing a photo of a painting and standing in front of the painting itself.

Third, there’s the completion of the circle. The story of Alice began in Oxford, was written in Oxford, was published while Carroll lived in Oxford. Having his personal copy return to Oxford creates narrative satisfaction. It’s like the book has come home after its own adventures (which, considering what happens in the book, is beautifully appropriate).

Fourth, there’s the access and preservation aspect. Christ Church and the Bodleian have the resources and expertise to preserve this book for centuries. They can maintain it, study it, and make it available to scholars and (in controlled circumstances) the public. They can digitize it, creating high-resolution scans that allow worldwide access while protecting the physical object.

This ensures that Carroll’s personal copy doesn’t just survive—it continues to contribute to scholarship and public understanding. It’s not locked away inaccessible; it’s actively part of literary culture.

Finally, there’s the inspiration factor. Having Carroll’s personal copy at Oxford inspires current and future students, scholars, and visitors. It’s a reminder that great literature comes from real people in real places. Students at Christ Church can study in the same halls where Carroll taught, walk the same gardens where he entertained the Liddell sisters, and now see his personal copy of the book that resulted from those experiences.

That’s powerful. It makes literary history feel immediate and accessible. It shows that creativity happens in real locations, and that legacy endures through physical objects and institutional preservation.

The Legacy That Won’t Stop Growing

Lewis Carroll died in 1898. It’s been over 125 years since his death, and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland shows no signs of fading into obscurity. If anything, it keeps gaining cultural relevance.

The book has been translated into over 170 languages. It’s been adapted into countless films, plays, ballets, operas, and video games. It’s influenced writers from James Joyce to Salman Rushdie. It’s been analyzed by mathematicians, philosophers, psychologists, and literary scholars. It’s inspired fashion, art, music, and memes.

Disney’s 1951 animated adaptation introduced Alice to generations of viewers who might never have read the book. Tim Burton’s 2010 film reimagined the story for contemporary audiences. The characters—the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter, the Queen of Hearts, the White Rabbit—have become cultural icons recognizable even to people who’ve never read Carroll’s work.

But it’s not just about adaptations and merchandising. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland legitimately changed children’s literature. Before Carroll, children’s books were primarily didactic—designed to teach moral lessons or practical knowledge. Carroll wrote purely for entertainment, embracing nonsense, wordplay, and imagination without requiring everything to have a moral.

This opened the door for authors like Roald Dahl, Dr. Seuss, and J.K. Rowling to write children’s books that were fun, weird, and imaginative without being preachy. Carroll showed that kids could handle complexity, appreciate wordplay, and enjoy stories that didn’t talk down to them.

His influence on literature extends beyond children’s books. The logical paradoxes and philosophical questions in Alice influenced the development of literary nonsense as a genre. The narrative structure—a journey through an absurd world that somehow makes its own internal sense—has been endlessly copied and reinterpreted.

Modern fantasy and surrealist fiction owe debts to Carroll. The idea that you can create a fully realized world with its own bizarre logic, that doesn’t have to conform to real-world rules but must be consistent within itself—that’s partly Carroll’s legacy.

The return of Carroll’s personal copy to Oxford is a reminder of all this. It’s not just about preserving an old book; it’s about honoring a legacy that continues to grow and evolve. Every new adaptation, every scholarly paper, every child reading the book for the first time adds to Carroll’s impact.

And having his personal copy at Christ Church—where it all started—creates a kind of literary pilgrimage site. Scholars and fans can visit the place where Alice was born, see where Carroll lived and worked, and connect with the physical object he owned. It makes the legacy tangible.

Coming Full Circle

There’s something beautifully appropriate about Carroll’s personal copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland returning to Oxford. The book tells a story about going on a strange journey and eventually finding your way back. And in a way, that’s exactly what the book itself has done.

Carroll’s copy left Oxford at some point after his death. It changed hands, possibly crossed oceans, survived over a century of history including two world wars. And now it’s back, preserved and celebrated at the institution where Carroll spent his life and where the Alice story was born.

It’s the kind of circular narrative that Carroll, who loved logic puzzles and patterns, would probably appreciate. The book has come home, completing its own adventure through time.

For Oxford, this return is a chance to celebrate one of its most famous literary connections. Carroll is part of Christ Church’s history, and having his personal copy in their collection strengthens that connection for current and future generations.

For scholars and fans, it’s an opportunity to engage with Carroll’s work in a new way—through the physical object he owned, in the place where he created it.

For the broader public, it’s a reminder of literature’s power to endure, to inspire, and to connect us across time. Carroll’s Victorian-era book continues to captivate readers in the 21st century, proving that great storytelling transcends its original context.

And for the book itself? Well, if books could have feelings (and in Wonderland, who knows), this one is probably happy to be home. Back in Oxford, back at Christ Church, back where a mathematics lecturer once told silly stories to children in a garden and accidentally created something immortal.

Welcome home, Alice. Oxford missed you.

Now, shall we celebrate with a tea party? Just, you know, a normal one. With time that actually moves forward and cups that get washed.

Though honestly, after 150 years, maybe a mad tea party is more appropriate.

Either way, the guest of honor is definitely invited.