The Question Everyone’s Been Asking Since the 1960s

Let’s address the elephant—or rather, the hookah-smoking caterpillar—in the room: Is “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” about drugs?

This question has been debated in dorm rooms, academic papers, and internet forums for decades. People point to the mushrooms, the bizarre transformations, the reality-bending experiences, and the general vibes of Wonderland and think, “This HAS to be about psychedelics, right?”

Here’s the thing: Lewis Carroll wrote this in 1865, well before the psychedelic movement of the 1960s. He was a Victorian mathematician and Anglican deacon—not exactly the profile of someone dropping acid and writing down the trip. But that hasn’t stopped generations of readers from seeing psychedelic symbolism throughout the text, and honestly? Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

The connections are compelling. Alice eats and drinks things that make her grow and shrink. She encounters a caterpillar smoking something on a mushroom who asks existential questions about identity. The logic of Wonderland operates on dream-like rules where anything can happen and usually does. Reality is fluid, perception is unreliable, and Alice spends most of the book trying to figure out who she is and what’s real.

Sound familiar? Because that’s basically a description of a psychedelic experience.

But here’s where it gets interesting: whether or not Carroll intended psychedelic symbolism, the imagery resonates with those experiences so strongly that the connection has become part of the book’s cultural legacy. The 1960s counterculture adopted Alice as a spiritual mascot, and references to Wonderland became shorthand for altered consciousness.

So was Carroll secretly encoding drug experiences into a children’s book? Probably not. Was he writing about consciousness, identity, perception, and the nature of reality in ways that happen to align with psychedelic experiences? Absolutely. And that’s what makes this worth exploring.

Let’s dive down the rabbit hole—responsibly, legally, and with lots of literary analysis. We’re going to explore the psychedelic symbolism in Wonderland, whether Carroll meant it or not, and why this interpretation has endured for over half a century.

Fair warning: this gets weird. But then again, so does the book.

The Caterpillar: Your Existential Crisis, Now With More Smoke

Let’s talk about one of the trippiest characters in all of literature: the Caterpillar. This guy shows up sitting on a mushroom, smoking a hookah, asking the most unsettling question possible: “Who are YOU?”

On the surface, it’s just a weird encounter. But look closer, and the Caterpillar scene is basically a masterclass in existential philosophy delivered by an insect on drugs (or at least, an insect that looks like it’s on drugs).

Alice meets the Caterpillar at a moment of crisis. She’s been growing and shrinking, losing her sense of self, forgetting who she is. She’s literally having an identity crisis, and the Caterpillar doesn’t help—he just makes it worse by forcing her to articulate it. “Who are you?” isn’t a simple question when you’ve been three different sizes in the last hour and can’t remember your own poems correctly.

The Caterpillar’s whole vibe screams altered consciousness. He’s perched on a mushroom—we’ll get to the significance of that in a minute—speaking in slow, deliberate sentences, asking profound questions in ways that seem both deeply meaningful and utterly cryptic. He’s detached, observant, and somehow both helpful and completely unhelpful at the same time.

His famous question forces Alice (and readers) to confront the fluidity of identity. Who are you when your physical form keeps changing? Who are you when the rules of reality keep shifting? Who are you when nothing makes sense anymore? These are the kinds of questions that keep philosophers and people in altered states of consciousness awake at night.

The Caterpillar is also literally going through transformation—he’s about to become a butterfly. So he’s asking Alice about identity while existing in a transitional state himself. The symbolism is almost too perfect: the guide to transformation is himself transforming, embodying the very journey he’s directing Alice through.

And then there’s the mushroom. Oh, the mushroom. The Caterpillar tells Alice that one side will make her grow, the other will make her shrink. It’s a size-altering mushroom given to a confused child by a smoking caterpillar. Victorian children’s literature, everyone!

The mushroom becomes Alice’s tool for navigating Wonderland. She uses it throughout the book to adjust her size, to fit through doors, to deal with the changing demands of her environment. It’s literal and metaphorical control over her experience—agency in a world that otherwise feels completely chaotic.

Whether Carroll intended this or not, the Caterpillar scene reads like a guide to consciousness exploration. The questioning of identity, the smoking figure on the mushroom, the advice about transformation, the tools for altering perception—it’s all there, encoded in a children’s book from 1865.

The 1960s counterculture saw this scene and said, “Yep, this guy gets it.” And while Carroll probably wasn’t thinking about psychedelics, he was absolutely thinking about consciousness, perception, and the malleability of self—themes that happen to overlap significantly with psychedelic experiences.

The Amanita Muscaria: Nature’s Red-and-White Mind-Bender

Now let’s talk about the specific mushroom that people associate with the Caterpillar scene: the Amanita muscaria, also known as the fly agaric. You know the one—bright red cap with white spots, looks like it came straight out of a fairy tale. Because it literally did. This mushroom appears in folklore, fairy tales, and traditional art across cultures, and it’s almost certainly the mushroom Carroll had in mind.

The Amanita muscaria isn’t just decorative—it’s psychoactive. It contains compounds called muscimol and ibotenic acid, which can cause altered states of consciousness, visual distortions, euphoria, and a sense of time dilation. Basically, it makes reality weird, which is very on-brand for Wonderland.

But here’s the important context: this mushroom has been used in shamanic practices for centuries, particularly in Siberian cultures. Shamans would consume it to enter altered states, communicate with the spiritual realm, and gain insights. It was sacred, ritualistic, and deeply embedded in cultural traditions long before anyone thought about recreational use.

The mushroom’s presence in folklore is extensive. It appears in Norse mythology, traditional European stories, and cultural practices across the Northern Hemisphere. It’s the mushroom that shows up in illustrations of fairy circles, gnome houses, and magical forests. It’s archetypal—the mushroom that says “something strange is about to happen.”

When Carroll put a caterpillar on a mushroom in Wonderland, he was tapping into this rich symbolic tradition. Whether he knew about the psychoactive properties is debatable, but he definitely knew the cultural associations. Mushrooms in Victorian literature often represented the mysterious, the transformative, and the otherworldly.

The effects of Amanita muscaria align eerily well with Alice’s experiences: altered perception of size (Alice grows and shrinks), distorted time (time doesn’t work right in Wonderland), surreal encounters (literally everything in the book), and a general sense that reality has become negotiable. These parallels are too striking to ignore, even if they’re coincidental.

Here’s what’s fascinating: whether Carroll knew about the mushroom’s properties or not doesn’t really matter for interpretation. The symbolism works. The connection between mushrooms, altered consciousness, and surreal experiences is so culturally embedded that Carroll couldn’t have used a mushroom without invoking these associations, even unconsciously.

The Amanita muscaria in Alice’s Adventures represents transformation, mystery, and the gateway to altered states—literally and metaphorically. It’s the tool Alice uses to navigate Wonderland’s changing demands, the symbol of her adaptability, and the visual representation of how consciousness and perception can be altered.

And let’s be honest: Carroll, being the meticulous author he was, didn’t choose a mushroom randomly. He chose something visually striking, culturally loaded, and symbolically rich. The fact that it happens to be psychoactive is either an incredible coincidence or evidence that Carroll knew more than his proper Victorian image suggests.

Either way, the mushroom stays. And it remains one of the most analyzed symbols in the entire book, a nexus point where Victorian literature meets shamanic tradition meets 1960s counterculture meets modern literary interpretation. Not bad for a fungus.

When Literature Gets Weird: Psychedelia in Art and Writing

Alice isn’t alone in literary history as a work that explores altered consciousness and surreal experiences. Let’s look at how psychedelic themes show up across literature and art, because understanding the tradition helps us see what Carroll was doing—and what later artists did with his work.

The Beat Generation writers embraced altered consciousness as a literary device and lifestyle choice. Jack Kerouac’s stream-of-consciousness prose in “On the Road,” Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” with its hallucinatory imagery, William S. Burroughs’ fragmented narratives—they were all exploring how to represent altered states in writing. They saw Alice as a predecessor, a Victorian text that somehow captured the essence of consciousness exploration decades before they tried it themselves.

The visual artists of the psychedelic era took this further. Think of the poster art of the 1960s—Victor Moscoso’s vibrating colors, Wes Wilson’s melting letterforms, Peter Max’s surreal landscapes. These artists were trying to recreate visual experiences of altered consciousness, and they consistently referenced Alice. The white rabbit became a symbol of going deeper into the experience. The caterpillar appeared in countless psychedelic posters.

What connects all this work—Carroll’s Victorian fantasy, Beat poetry, and 1960s visual art—is an interest in depicting consciousness itself. Not just what characters think, but how perception works, how reality can shift, how identity becomes fluid under certain conditions.

Carroll’s genius was making this accessible and engaging. He wrapped consciousness exploration in a children’s adventure story, making it entertaining while encoding deeper philosophical questions. The Mad Hatter isn’t just a character—he’s a representation of how logic breaks down in certain states. The Cheshire Cat’s appearances and disappearances mirror how perception can fragment and reform.

Modern authors continue this tradition. Haruki Murakami’s surreal narratives, Neil Gaiman’s dreamlike fantasies, Jeff VanderMeer’s ecological weird fiction—they’re all descendants of what Carroll started. They use fantastical elements to explore consciousness, identity, and perception, knowing that sometimes the best way to talk about reality is through unreality.

The connection between psychedelic art and Carroll’s work runs both ways. The 1960s counterculture adopted Alice because the symbolism was already there. But that adoption also changed how we read Carroll—once you see the psychedelic interpretation, it becomes part of the text’s meaning, even if Carroll never intended it.

This is how cultural interpretation works: meanings accumulate, symbols gain associations, and texts become richer through the lens of history. Alice now exists in multiple contexts—as Victorian children’s literature, as mathematical and logical paradox, as social satire, and as exploration of consciousness. All of these readings are valid because all of them illuminate something true about the text.

What Was Carroll Really Saying?

Okay, let’s get serious for a moment. What was Lewis Carroll actually trying to communicate with all this surreal imagery?

At its core, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” is about consciousness, identity, and perception. Alice spends the entire book trying to figure out who she is, what’s real, and how to navigate a world where the rules keep changing. That’s not just a plot—it’s a philosophical inquiry disguised as children’s entertainment.

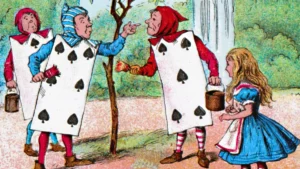

Every character Alice meets represents a different aspect of experience or a different challenge to her understanding of reality. The Cheshire Cat talks about madness and sanity being relative. The Mad Hatter demonstrates how arbitrary social conventions can be. The Queen of Hearts shows how authority can be both absolute and absurd. The Caterpillar asks the fundamental question: who are you, really?

Carroll was writing during Victorian England, a time of massive social change, scientific advancement, and philosophical upheaval. Darwin had recently published “On the Origin of Species,” challenging fundamental ideas about human identity. Industrialization was transforming daily life. Traditional certainties were becoming negotiable.

Wonderland reflects this instability. Nothing is fixed. Identity is fluid. Size is relative. Time doesn’t work properly. Logic leads to paradoxes. It’s a world where the only constant is change, and Alice has to learn to navigate it without any reliable guides or rules.

The psychedelic interpretation resonates because psychedelic experiences often involve similar themes: questioning identity, experiencing reality as fluid, confronting the arbitrary nature of social constructs, and grappling with profound questions about consciousness and existence. Whether Carroll knew about consciousness-altering substances or not, he was writing about consciousness-altering experiences.

What makes Carroll’s work transcendent is that it operates on multiple levels simultaneously. Children enjoy the adventure and the weird characters. Teens appreciate the rebellion against adult authority and rigid rules. Adults recognize the social satire and philosophical depth. And everyone, at every level, encounters questions about identity and reality that never stop being relevant.

The nonsensical logic of Wonderland isn’t random—it’s carefully constructed to provoke specific kinds of thinking. Carroll was a logician, remember. He knew exactly what he was doing when he created a world where logical principles lead to absurd conclusions. He was showing that logic itself has limits, that reason can’t answer every question, and that sometimes you have to embrace uncertainty.

This is why the psychedelic interpretation works even if it wasn’t intended: because Carroll was genuinely exploring consciousness, perception, and the nature of reality. The tools and imagery he used to do this—transformation, altered states, identity crises, reality becoming negotiable—happen to overlap with psychedelic experiences. It’s convergent evolution in symbolic language.

Carroll’s message, ultimately, is that reality is more complex than we assume, identity is more fluid than we pretend, and consciousness is stranger than we typically admit. Wonderland is what happens when you peel back the comfortable illusions we use to navigate daily life and confront the actual weirdness of existence.

Whether you get there through literature, philosophy, or altered consciousness doesn’t really matter—the questions are the same, and they’re the questions Carroll wanted us to ask.

The Enduring Trip

So is “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” about drugs? No. Is it about consciousness, perception, reality, and identity in ways that resonate strongly with psychedelic experiences and symbolism? Absolutely.

Carroll gave us a text rich enough to support multiple interpretations, including ones he never anticipated. The psychedelic reading became part of the book’s legacy because the symbolism was there to be found—mushrooms, transformation, identity crises, reality becoming fluid, profound questions about consciousness and existence.

The 1960s counterculture saw themselves in Wonderland because Carroll had written something universal about human experience. The specifics change—Victorian anxieties about industrialization, 1960s exploration of consciousness, modern concerns about reality and identity in digital age—but the fundamental themes remain.

What makes great literature isn’t intention—it’s depth. Carroll created something deep enough that generations keep finding new meanings, and those meanings are valid because they illuminate something true about both the text and human experience.

The psychedelic interpretation doesn’t diminish other readings. It adds to them. Alice can be simultaneously a children’s adventure, a logic puzzle, a social satire, a philosophical inquiry, and an exploration of consciousness. Great art contains multitudes.

So whether you read Wonderland as Victorian literature, mathematical paradox, social commentary, or psychedelic symbolism—you’re right. All of these readings are there, waiting to be explored. The rabbit hole goes as deep as you’re willing to follow it.

Carroll wrote about the strangeness of consciousness, the fluidity of identity, and the negotiability of reality. He did this through mushrooms, caterpillars, tea parties, and playing cards. Whether he knew he was creating a text that would resonate with psychedelic culture is almost beside the point.

He created something true about how consciousness works, how identity shifts, and how reality isn’t as solid as it seems. And truth, once written down, takes on a life of its own.

Welcome to Wonderland. It’s been waiting for you, one way or another, since 1865. The caterpillar has questions. The mushroom has lessons. And Alice is still trying to figure out who she is.

Aren’t we all?

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go contemplate my identity while sitting on a mushroom. For research purposes. Strictly literary analysis.

The caterpillar would approve.