The Girl Who Started It All

Let’s talk about Alice Liddell—the actual Alice. Born in 1852 in Westminster, she was essentially living the Victorian equivalent of growing up in an Ivy League college town. Her dad was the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, which meant she had the kind of childhood where brilliant minds were just… around. No big deal.

Enter Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll), family friend and chronic storyteller. When he met the Liddell kids in 1856, he was immediately charmed. But Alice? She was special. Curious, playful, with an imagination that could rival any adult’s—she was basically the perfect muse for someone who’d eventually write one of the trippiest children’s books in history.

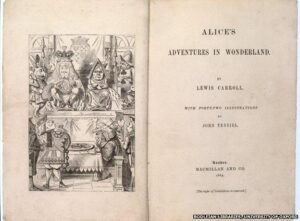

Their friendship was built on river outings and wild tales. That famous boat trip in July 1862? That’s when Carroll spun the story that would become “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” Picture it: a sunny afternoon, a boat gliding down the Thames, and Carroll making up increasingly bizarre scenarios while Alice and her sisters hung on every word. It was part improv session, part babysitting, and entirely magical.

The real Alice’s adventurous spirit and endless “but why?” questions gave Carroll exactly what he needed: a character who’d question everything in Wonderland without losing her mind (well, mostly). She’s the straight man in a world of absurdity—and that only works because the real Alice had that perfect mix of wonder and “okay, but seriously?”

The Red Queen: When Your Headmistress Gets a Crown

If you’ve ever had a teacher who seemed to live for strict rules and public humiliation, congratulations—you’ve met the Red Queen. This character from “Through the Looking-Glass” is basically Victorian authority on steroids, and honestly? She’s terrifying in the most delightful way.

Carroll (remember, his day job was as a mathematics lecturer at Oxford) was surrounded by rigid, no-nonsense authority figures. Think stern headmistresses, uptight church officials, and educators who believed children should be seen, not heard, and definitely not enjoying themselves. The Red Queen, with her “Off with their heads!” catchphrase, is what happens when you take Victorian strictness and crank it up to eleven.

But here’s the genius part: she’s not just scary. She’s also kind of ridiculous. Her constant demands for order in a fundamentally chaotic world? That’s Carroll poking fun at the Victorian obsession with rigid social hierarchies and moral codes. In a society where your table manners could make or break your reputation, the Red Queen’s tyranny hits different—it’s satire with a side of social commentary.

The woman doesn’t just want obedience; she wants immediate obedience, which honestly sounds like every stressed-out authority figure trying to maintain control in an uncontrollable situation. Carroll saw that tension and turned it into pure literary gold.

The White Queen: Femininity’s Hot Mess Era

Now, the White Queen is where things get interesting. She’s everything the Red Queen isn’t—gentle, somewhat scattered, and living in a state of perpetual confusion. If the Red Queen is “I want to speak to the manager,” the White Queen is “Wait, I am the manager?”

Carroll created her as a counterpoint to explore the weird, contradictory expectations Victorian society had for women. Ladies were supposed to be pure, gentle, and submissive—but also strong enough to run households and raise children. They should be educated, but not too educated. Accomplished, but not ambitious. The White Queen embodies all these contradictions at once, and she’s kind of a disaster because of it.

Think about the women in Carroll’s life—educated, intelligent women who had to navigate a society that simultaneously valued and limited them. The White Queen, living backward in time and offering Alice advice that makes no sense, is Carroll’s way of showing how impossible these expectations were. She’s trying her best, but the rules keep changing, and honestly, who can keep up?

There’s something deeply relatable about her chaos. She’s feminine, yes, but she’s also human—flawed, confused, and doing her best in a world that doesn’t quite make sense. Sound familiar?

The Mad Hatter: Your Weird Uncle, But Make It Literature

Ah, the Mad Hatter. Everyone’s favorite unhinged tea party host. But did you know he might be based on a real person? Meet Theophilus Carter, a furniture dealer in Oxford who was known for two things: hosting strange tea parties and wearing some truly questionable hats.

Carroll took one look at this guy and thought, “Yeah, this is perfect for my weird book.” But the Hatter isn’t just a quirky character—he’s also a dark commentary on mental health in Victorian times. The phrase “mad as a hatter” comes from the hat-making industry, where workers developed neurological problems from mercury exposure. They literally went mad from their jobs, and society’s response was basically, “Huh, weird,” and then moved on.

The Hatter’s endless tea party—stuck in time at 6 o’clock—is both absurd and kind of tragic. He’s trapped in a loop, unable to move forward, making small talk about nothing with his equally odd companions. It’s social commentary disguised as nonsense, and it’s brilliant.

Carroll transformed his friend’s eccentricities into a character that makes us laugh while also making us think. The Hatter’s “madness” isn’t threatening—it’s creative, playful, even liberating. Maybe, Carroll suggests, the “mad” ones are the only sane people in an insane world.

Hatta: The Mad Hatter’s Darker Twin

In “Through the Looking-Glass,” Carroll gives us Hatta—basically the Mad Hatter’s mirror image, but with more anxiety. While the Hatter is chaotic fun, Hatta brings a dose of existential dread to the party.

This is Carroll playing with the concept of duality. Same person, different world, different vibe. Hatta is what happens when you take the Hatter’s eccentricity and add a layer of self-awareness and vulnerability. He’s still weird, but now he knows he’s weird, and he’s not entirely comfortable with it.

The relationship between these two characters is fascinating because it forces us to ask: what makes someone “mad”? Is it how they act, or how society perceives them? Hatta’s interactions with Alice show someone trying to navigate a world that doesn’t quite accept him, which, let’s be honest, is pretty much everyone’s experience at some point.

Carroll uses Hatta to explore identity in a way that feels surprisingly modern. We’re all performing different versions of ourselves depending on context, right? Hatta and the Hatter are just the literary version of your work self versus your weekend self.

The Caterpillar: Philosophy’s Smoking Section

“Who are YOU?” asks the Caterpillar, and honestly, same. This hookah-smoking philosopher sitting on a mushroom is Carroll at his most existential. The Caterpillar doesn’t just ask questions—he asks the questions. The big ones. The “what does it all mean” ones.

Victorian England was having a moment with philosophy. John Stuart Mill was talking about utilitarianism, people were questioning traditional beliefs, and generally, everyone was having an identity crisis. The Caterpillar, with his detached wisdom and transformative lifestyle (caterpillar to butterfly—get it?), embodies all of this.

Carroll might have drawn inspiration from intellectuals in his circle—people like Thomas Huxley or the Pre-Raphaelite artists who were all about questioning convention and seeing the world differently. The Caterpillar’s whole vibe—the smoking, the cryptic advice, the fundamental question of identity—screams “I’ve read philosophy and now everything is a question.”

But here’s what makes the Caterpillar brilliant: he’s annoying. Alice finds him frustrating, and so do we. Philosophy can be like that—all profound questions and no straight answers. Yet somehow, he helps Alice figure things out. Sometimes the most irritating teachers are the most important ones.

Carroll’s Squad: The Original Found Family

Let’s zoom out for a second. Carroll wasn’t creating these characters in a vacuum. He was surrounded by fascinating people—kids, academics, eccentrics, and everything in between. Oxford in the Victorian era was basically a petri dish of interesting personalities, and Carroll was taking notes.

Alice Liddell and her sisters were obviously huge influences, representing childhood innocence and curiosity. But Carroll’s academic colleagues? They’re in there too. The Mad Hatter might be Theophilus Carter, but the character also reflects the playful intellectual debates Carroll had with his friends.

The Cheshire Cat, with his philosophical musings about madness and logic, probably came from countless late-night discussions about reality and perception. The Queen of Hearts, with her arbitrary cruelty, might reflect Carroll’s observations about power and authority in Victorian society.

Even the minor characters—the Duchess, the Mock Turtle, the Gryphon—they’re all little pieces of people Carroll knew or observed. It’s like he was running a social experiment: “What if I took everyone I know and put them in a blender with some absurdist humor and social commentary?”

The result? A cast of characters so vivid and strange that they’ve outlived everyone who inspired them. Not bad for a guy who just wanted to entertain some kids on a boat trip.

Alice’s Eternal Glow-Up

Here’s the thing about Alice Liddell’s legacy: she became immortal. Not bad for someone who was just a kid listening to stories on a river.

Since 1865, Alice has been everywhere. Disney turned her into an animated icon. Tim Burton gave her a goth makeover. Fashion designers have been riffing on her blue dress for decades. She’s in art, literature, music, memes—you name it, Alice has been there.

Writers like Thomas Pynchon and Salman Rushdie have used Wonderland as a framework for exploring reality and identity. Alice’s journey—a kid trying to make sense of an absurd world—resonates because, well, isn’t that all of us? The specifics change, but the feeling of being lost in a world that doesn’t quite make sense? That’s timeless.

Fashion has particularly embraced Alice. That blue dress and white apron combo has been reinterpreted by designers from high fashion to Hot Topic. She represents this perfect mix of innocence and rebellion, prim and punk, traditional and transgressive. She’s a blank canvas that every generation paints in their own colors.

Modern coming-of-age stories owe a lot to Alice. She paved the way for characters who question authority, explore strange new worlds, and try to figure out who they are in the process. Every young protagonist navigating a confusing world is a little bit Alice.

Where Fantasy Meets Reality (And Gets Weird)

So here’s what makes Carroll’s work so enduring: he understood that the best fantasy is rooted in reality. All those bizarre characters? They’re not just random weirdness—they’re people he knew, observations he made, and critiques he wanted to make, all dressed up in absurdist clothing.

Carroll took the Victorian world—with its rigid rules, bizarre social expectations, and often hypocritical morality—and said, “What if I just… made this slightly more surreal?” The result shows us that the “real” world was already pretty strange.

The characters of Wonderland are mirrors. They reflect society back at us, but with the contrast turned way up so we can actually see what’s happening. The Red Queen’s tyranny? That’s real authority, just more honest about it. The Mad Hatter’s chaos? That’s creativity trying to survive in a world that values conformity. Alice’s confusion? That’s all of us, all the time.

This is why these characters still matter. They’re not just Victorian relics—they’re archetypes. We all know a Red Queen (probably works in HR). We’ve all felt like the White Queen (especially on Monday mornings). We’ve all wanted to have tea with the Mad Hatter (or maybe we already do, just on Zoom now).

Carroll’s genius was recognizing that reality is strange enough—you just have to tilt your head and look at it from a different angle. His creativity wasn’t about escaping reality; it was about seeing it more clearly by dressing it up in a rabbit costume and sending it down a hole.

The Takeaway: We’re All Mad Here

At the end of the day, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” reminds us that the line between reality and fiction is fuzzier than we like to admit. The people who inspired these characters were real, with their quirks and contradictions and complexities. Carroll just turned up the volume.

What makes these characters immortal isn’t that they’re completely fantastical—it’s that they’re completely human, just filtered through a lens of creative absurdity. They make us laugh, make us think, and make us see our own world a little differently.

So the next time you encounter someone who seems like they stepped out of Wonderland—whether it’s an overly authoritative boss, a charmingly scattered friend, or someone whose logic seems to operate on a different plane—remember: they might just be the next great literary character. All they need is someone with enough imagination to see the story hiding in the ordinary.

After all, we’re all mad here. Some of us just have better hats.